Peer support: how ordinary Ohioans are helping others break mental health barriers

Four years ago, Rondye Brown reached “the darkest place” in his life. Feeling trapped in an endless cycle of crime, prison and substance abuse, Brown decided on what he believed to be his best solution.

“I asked God to remove his hand from me, because I didn’t want to be in a conscious state of feeling,” he recalled. “When I said that to God, I knew that I was going to end my life.”

Alone in his room that night at a friend’s house in Southern Ohio, Brown grabbed a knife and stabbed himself in the chest. When he regained consciousness a few hours later, he looked down at a pool of blood. He also saw the knife and knew he needed to remove it.

He called a couple of friends from church, and they drove him to the hospital. There, he learned he had missed his heart by two inches.

Brown, 50, was born into a dysfunctional family in Cleveland. His mother’s alcoholism, his father’s death when he was a boy, and ongoing mental and physical abuse warped his youth. When he called his sister, she told him she had suffered the same abuse, but she finally sought medical care to address her mental health.

“A lot of bad things happened in our family,” Brown said. “I grew up seeing it and imitating it, costing me many years in prisons and mental institutions. I had used every substance possible to suppress all of my anger about everything I went through as a child and in jail until I gave up hope on my life that night.”

Drawn by his sister’s pleas for him to seek help, he took a cab to Cleveland. While recuperating in MetroHealth Medical Center, Brown met a peer supporter for Thrive Peer Recovery Services. A peer supporter, a person who is in recovery but has maintained sobriety for two years, is trained by Thrive to use their experiences with addiction to support others.

Brown’s peer supporter, Willie Richardson, spent two years helping him overcome his alcohol and substance dependency and his anxiety disorder, which made it difficult for him to catch a bus or take an Uber.

After about two years, Richardson helped Brown land a job as a dishwasher in a small MidTown cafe in Cleveland. Shortly afterward, he asked if he could be considered for a position as a peer supporter, and Thrive hired him.

Part of a growing movement, Thrive employs peer supporters to help people reduce social isolation and address their mental health needs as the foundation necessary to recover their economic and personal health.

For example, total calls to the Peer Support Warmline, which Thrive operates, have increased from just over 33,000 in 2019 to nearly 60,000 in 2021.

Started in 2019 with funding from Cuyahoga County’s Alcohol, Drug, Addiction and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) Board, Thrive provides peer support in several Cleveland hospitals. The organization has served more than 1,000 people since 2020, both in person and virtually.

The primary goal is to recover the individual’s health and life before they can even consider applying for or holding a steady job. When the person is ready, they can take resume writing, job interviewing, professional communication, conflict resolution, personal finances and other employment-specific programs to help them pursue work.

Additionally, the ADAMHS Board funds two employment services programs that include the Jewish Family Services Association and Recovery Resources. In 2021, the two agencies placed 285 clients into jobs.

Currently, the state of Ohio does not track utilization numbers for people hired after working with a peer supporter.

New: Read our “Eye on Utilities” Newsletter

Thrive thriving in Ohio

Since its founding in Cleveland in 2018, Thrive serves 66 of Ohio’s 88 counties. Co-founded by CEO Brian Bailys and COO Bridgette Lewis, the organization started with six employees and now numbers more than 150. Thrive is certified by Medicaid, so peers receive free services. Peer supporters use their personal stories to inspire, support, and provide insights into recovery.

Bailys’ son, Brandon, is the clinical director for Thrive. He oversees the community program and, like his father, struggled with mental health issues.

“People come to us in different stages of recovery and we support them in getting where they want to be,” Brandon Bailys said. “We do that in three main ways: We identify the support resources in the community they may need; we assist them in accessing those resources; and, ultimately, we empower them to access those resources independently.”

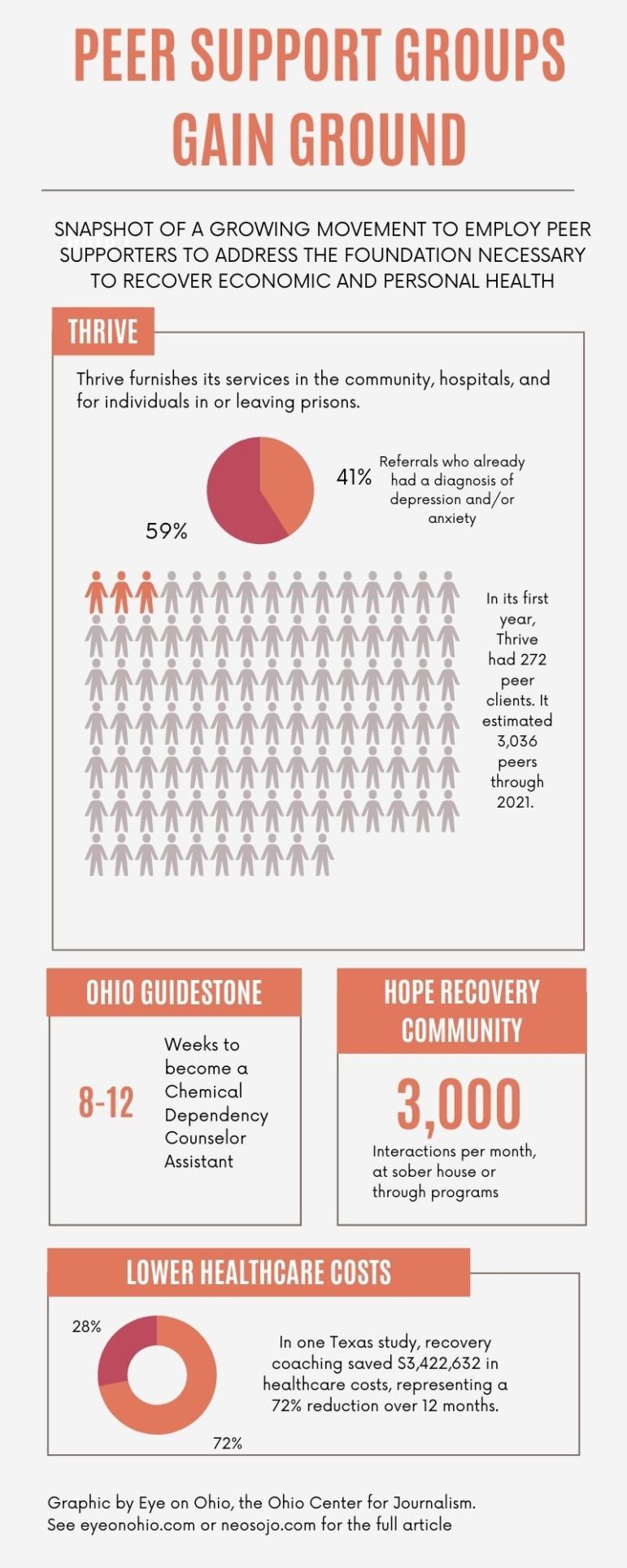

The field of peer support continues to grow, because it has demonstrated its efficacy by decreasing hospitalizations, prison reentry and cost to the payers, he said. One long-term study focusing on peer support specialists for substance abuse in Texas, for example, showed that recovery coaching saved $3,422,632 in healthcare costs, which was a 72-percent reduction in costs over 12 months.

Brown’s recovery wasn’t easy, but he quickly developed a relationship with Richardson, who always answered his phone when Brown needed help. Richardson spent a lot of time with him, and connected him with Thrive’s more than 50 community partners who provide a range of services. He also helped Brown find a job. Most importantly, he taught Brown the Golden Rule of recovery: “No matter what, don’t use.”

“We can move on and leave the past,” Brown said. “When we’re dealing with issues, we can talk about them, and we don’t have to drink and drug over what happens to us. You don’t have to hurt anymore, and you don’t have to suppress it with anything.”

Additionally, Thrive maintains partnerships with 24 hospitals throughout Ohio and expects to add two more by the end of this year. University Hospitals initiated its partnership with Thrive in late 2019. The plan was to have peer supporters available in all of its Emergency Departments, but the pandemic forced the hospital to go virtual for a while. Currently, UH makes the peer supporters available live when possible and virtually when not.

“Not only are we offering these patients more and able to get them better outcomes, but it has greatly improved the morale in the ED because we are able to do things that we couldn’t before,” said Ryan Marino, MD, addiction expert and emergency medicine physician at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

Jeanne Lackamp, the director of the Pain Management Institute at University Hospitals, agreed.

“They’re helping us save lives,” Lackamp said.

Medina’s Hope Recovery Community focuses on regaining personal happiness

In Medina, another peer support group, the Hope Recovery Community, offers people in recovery help with a different facet of their lives: finding safe ways to reclaim all of their favorite activities.

“We look at the whole person, and we say, ‘OK, how do we connect people back into their hobbies and passions,’ and so that they can enjoy them with friends,” said Stephanie Robinson, founding executive director.

In recovery from drugs, alcohol, and an eating disorder for more than 13 years, Robinson described the center as a recovery community organization and an independent nonprofit composed of people who have had personal lived experience with substance use disorder.

“That’s what makes up the majority of our board,” she said. “So we’re an organization made up of people in recovery that serves people in recovery.”

Robinson and her team started Hope Recovery Community in the fall of 2018 in response to the opioid and addiction crisis. The Medina County ADAMH Board bought a house, which opened in the fall of 2019. The house serves as the centerpiece of the organization.

The house is open seven days a week, 365 days a year, from 7 a.m. until 8 p.m. or midnight on weekends. It offers a haven for people in recovery and family members impacted by addiction where they can get connected to support, resources and community.

Robinson said HRC provides no clinical services and does not have patients or clients, only guests and friends. She estimated that the facility has about 3,000 “recovery touches” each month, which includes repeat visitors who come to the house to relax and get away from the pressures of their home situations.

On a typical weekday, the place sees 40-to-80 people, with 50-to-150 people on Saturday or Sunday.

The center also offers 25 to 30 hours a week of meetings and intentional programming. HRC’s guests have access to about 15 different pathways of recovery, from AA, NA, and HA recovery meetings to sessions for meditation, 12-step yoga, eating disorders, and refuge recovery to the purely fun activities like gardening, fishing, bowling, arts and crafts, Bingo, and even two sober Browns Backers groups.

“There’s always something going on, plenty of food, people playing Yahtzee or other games or just chilling all day,” Robinson said. “It’s like the party house that a lot of us used to know but without the dangerous party.”

In late November, HRC launched its Recovery Life Skills Institute, which will furnish 12 courses over the next year to give people in recovery key life skills that they might have missed while in active addiction. The focus will be on how to maintain and manage financial stability, their job, relationships, physical, mental health, spiritual health, their homes and children, etc.

OhioGuidestone offers numerous community services

HRC regularly connects guests to one of its community partners, OhioGuidestone. The behavioral health agency provides community-based services, including educational programs and coaching for all ages, and mental health and residential care.

Its Workforce Development program targets people in recovery to build on their personal addiction experiences. The 8- to 12-week program enables them to become certified as a chemical dependency counselor assistant, for example.

Robinson said that helps increase the growing recovery-oriented infrastructure necessary in all communities to help people achieve and maintain their return to a healthy, productive lifestyle.

She said society is starting to understand the needs of people with substance-use disorders, incorporating them into critical discussions and making them part of the solutions.

Brandon Bailys agreed. He said one of the limitations of the peer-support field is finding enough recovered people who want to support others in their recovery.

“Our workforce is small in that way,” he said. “Right now, it’s hard to retain anybody because there are career opportunities everywhere else. This field can also be so taxing personally, so having an available workforce has been a real challenge for us.”

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including Eye on Ohio, which covers the whole state.